The epoch of Yayoi (400 BC to 300 AD)

The epoch of Yayoi, spanning from approximately 400 BC to 300 AD, marks a momentous juncture in the annals of Japan's history.

This epochal period bore witness to the inception of rice cultivation within the Japanese archipelago and the nascent emergence of sedentary communities. It also bore testament to the existence of the illustrious Yamatai kingdom, which was presided over by the legendary sovereign, Princess Himiko.

A Pivotal Discovery in the Environs of Tokyo

The eponym of the Yayoi era, Dr. Arisaka Shozo, deserves recognition for his seminal discovery. In March of 1884, during archaeological expeditions conducted in the precincts of Tokyo's "Yayoi-cho" in the Bunkyo district, Dr. Shozo unearthed a distinctive variety of pottery. These newly unearthed ceramic artifacts, characterized by their finer craftsmanship and enhanced intricacy, diverged conspicuously from the ceramics conventionally ascribed to the preceding Jomon era (13,000 BC to 400 BC). The nomenclature "Yayoi" was bestowed upon this epoch, in resonance with the season of spring in the Japanese calendar, thus commemorating the period's advent.

Korean Influences on Japanese Soil

The Yayoi epoch owes much of its defining attributes to the palpable influences emanating from the Korean peninsula. Agriculturalists hailing from the Mumun culture, nestled within the confines of contemporary South Korea, traversed the intervening straits and settled both in Kyushu and the environs of Tokyo.

In consort with the autochthonous denizens of the Jomon era, these settlers ushered in a culture centered around rice cultivation, an endeavor demanding a surfeit of toil. This transformative shift facilitated the concentration and sedentarization of communities within expansive villages. The denizens of Yayoi Japan also embarked on the cultivation of an array of cereals, including millet, wheat, barley, and buckwheat.

Beyond innovations in agricultural systems, the period also bore witness to significant advances in the domains of metallurgy and ceramics. The Korean immigrants introduced the rudiments of ceramics to Japan, thereby paving the way for the creation of receptacles for rice storage and kitchen implements capable of withstanding temperatures exceeding 600 degrees Celsius.

Simultaneously, iron and bronze were introduced to Japan, heralding the advent of weapons (such as daggers, swords, and spearheads), tools (including axes and sickles), and ornamental bells known as dotaku. These ornate bells were often adorned with depictions of hunting scenes, wildlife, or scenes of everyday labor, and have been unearthed in numerous ritualistic deposits, predominantly dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.

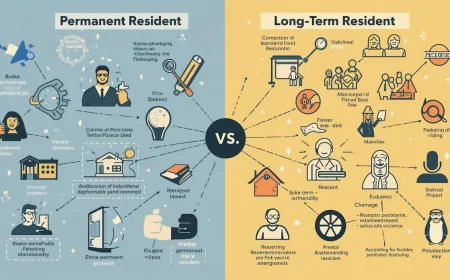

The Genesis of New Social Strata

The cultivation of rice in flooded paddy fields necessitated the construction of extensive canal networks to regulate irrigation, encompassing both drainage and supply canals. Concurrently, the agglomeration of inhabitants led to the gradual introduction of social differentiations, which are palpable through disparities discernible in burial customs, with some graves being conspicuously more opulent than others.

The burgeoning communities reached a size that facilitated their engagement with foreign lands. The last extant document attesting to interactions between the Yayoi of Japan and China dates back to the Han dynasty of China, documented in the Book of the Later Han. These records, from the year 57 AD, recount how the Wa people, the Chinese appellation for the Japanese, regularly dispatched tributary envoys to the representatives of the Chinese empire. Moreover, the annals of Wei Zhi expound upon the diplomatic relations between the Chinese Kingdom of Wei (220-265) and the realm of Yamatai, under the stewardship of the priestess Himiko.

記事に関連する商品